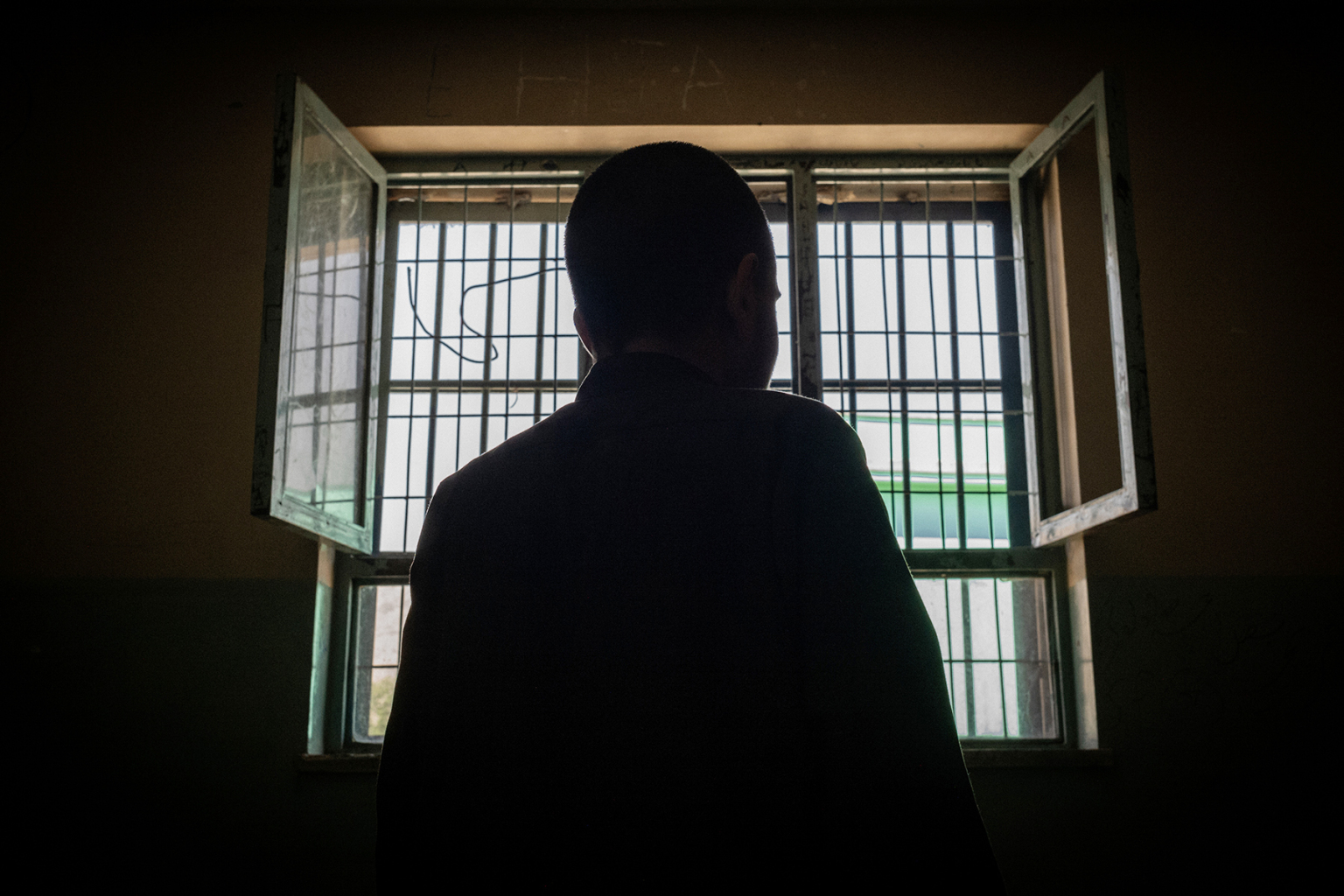

In a room full of loud teenagers, 17-year-old Mohammad Ehsan is the quietest. (The names of the boys in this piece have been changed to protect their identities.) The other boys in this juvenile rehabilitation center in the Afghan capital of Kabul are rough and boisterous; he takes the corner-most seat and avoids making eye contact. He speaks only when spoken to, sometimes answering with just a single word. As we talk, he stares at the floor or fidgets with the corner of his white shalwar kameez, as though he would rather be anywhere else than here.

His silence and his fear were hard-learned. Ehsan is one of 27 teenagers in this facility recruited and trained by the Taliban or the Islamic State to plant improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in the country’s endless war. Some, including Ehsan, were held in the Bagram prison located outside of Kabul, formerly operated by the United States. The other children are afraid of associating with them. “They’re too political and dangerous,” a young man incarcerated for murder said.

IED use surged in Afghanistan last year, killing or injuring 3,043 people. Children like Ehsan are particularly valued as bombers, their youth and size giving them cover during the stealthy planting of IEDs. At the facility, we’re introduced to seven of them, all between 13 and 17 years old—not all bomb planters but who were used in a variety of military roles by the Taliban.

A report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) in 2016 noted that the Taliban had been training and deploying teenagers for a range of military operations, especially for the placement of IEDs. The number of such recruits has soared since then. U.N. reports about the siege of Kunduz province in 2015 indicate that the Taliban used underaged child soldiers, some as young as 10 years old, as front-line soldiers. “The surge [of using children for insurgencies] began in mid-2015 as the Taliban made gains in areas they had not previously controlled, particularly in the northeast,” explained Patricia Gossman, the author of the HRW report and the group’s associate director in Afghanistan.

He was born only a few weeks after the United States first sent troops into Afghanistan, and his early years, which he remembers happily, were spent among the relative peace and quiet that followed the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001. The oldest of the two sons of a pious family from eastern Afghanistan, his early education was at a school that opened not long after the U.S. occupation and was close to a U.S. provincial reconstruction team.

When he was 13 years old, though, Ehsan was approached by his uncle, he said, and asked to come with him. “I trusted him because he was my uncle. I had no idea he worked for the Taliban. … He took me to the Taliban, and they asked me to plant bombs in the city since, as a kid, I wouldn’t attract a lot of attention. When I refused, they beat me several times. I was so afraid,” he said, insisting, and later swearing on his life, that he was not a Taliban member himself.

Ehsan planted two roadside bombs in his district that claimed the lives of six civilians and injured eight others. He was caught soon after the attack. While being held in a local prison in his district, he met with the children of one of the men his bombs had killed. “They came to see me in jail. They were about my age. We didn’t talk, but it was a very painful moment,” he said, his face hard to read. Ehsan was later moved to the U.S.-built Bagram prison, where he was kept with others accused of working with the Taliban. When under U.S. control, it had a reputation for the abuse of inmates—which has reportedly barely changed since the Afghan government took over in 2013. “It was a difficult experience. They weren’t nice to us, and they sprayed us with poison gas that would make us unconscious,” he claimed, perhaps referring to tear gas or other riot control methods. “I was there for nearly 20 months and didn’t even get to see my family even once in that time.”